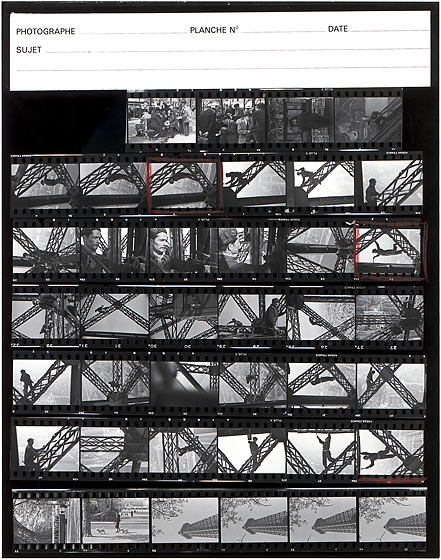

Choice and freedom of choice is not just an existential concern for photographers. It is a life-time preoccupation. We spend more time squinting through a magnifying glass, fretting over our contact sheets, than we do looking through the viewfinder of our camera. And the muscles of our eyes suffer as much as those of the Amsterdam diamond cutters and of the watchmakers from our childhood.

Impulse, reflex, aim… one hundredth of a second for a look, a click: but hours of patience to choose the right photo.

Should we publish these « contacts », this inventory of all the winks our camera made? Should we show our drafts, our sketches, open our notebooks full of secrets and hesitations? Should we let you hear the false note we make while searching for the right key, the right image?

How many tens of hundreds of photos for one good one? Judging by the number we take, a layman will often say: “You’re bound to have a good one there!” With the increasing use of the motor-drive, this sort of comment is even more inevitable. The fast repetition of shots enables you eventually to hit a target, but does it really help to make a better picture? I don’t think so. (…) A billion shots will not increase the chance for a monkey to produce a Kertész or a Doisneau. Indeed the motor-driven camera has helped the documentation of events, but has it improved the quality of photography?

How do we make our choice? Of course primarily by judging the structural balance and harmony of the plastic composition as well as of the content. Choice is also influenced by our mood and by the contradictory advice of competent friends and colleagues. But most often the best photo instinctively catches our eyes just as a pleasing melody captivates our ear.

Our taste, our choice, vary with time. When I look at photos I took 30 years ago, it’s with different, almost foreign eyes. A selection made in the heat of the moment, right after a journey, may be affected by emotional warmth, a commitment, likes and dislikes that will fade with the years.

In the end, the photographer alone must make and assume his choice. For him, this choice is the means of expression that ultimately helps define his style.

Marc Riboud